One of the questions we get at Strategyn involves the application of Jobs-to-be-Done Theory to Government.

Can JTBD be used to help government agencies do a better job? We’ve used JTBD with government agencies to help them better understand their service levels, their delivery models, and how to get closer to the customer – you, the citizen.

The Purpose of Government

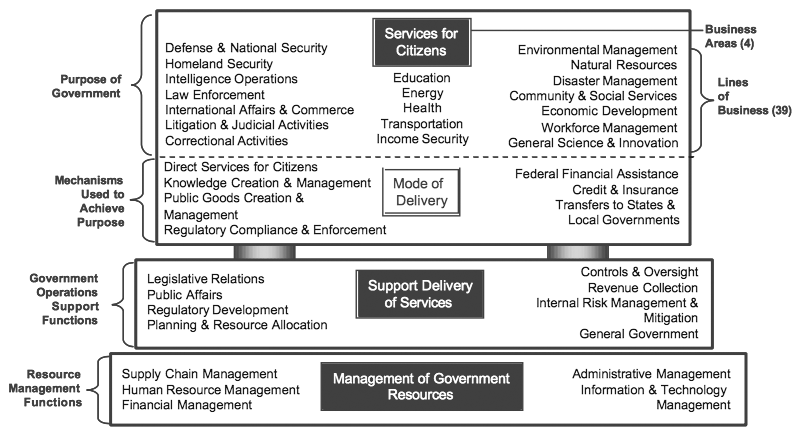

The process starts with a exploration of the mission of government, and the agency or department. At the highest level, we can illustrate the purpose of government using the business reference model:

The problem with this Federal Enterprise Architecture (FEA) is that it uses a centralized service infrastructure that is not designed around customer needs, i.e. the needs of citizens.

The current conventional wisdom that liberals are pro-government and conservatives are anti- is frequently traced to President Ronald Reagan’s often-invoked notion that government is the problem, not the solution. But when you read Reagan’s first inaugural address, delivered in 1981 in the middle of a crushing recession, what he actually said was this: “In this present crisis, government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.” This was not a blanket condemnation of government, but a reaction to a specific situation in which the federal government seemed particularly ineffective. Reagan went on to say that “it’s not my intention to do away with government. It is rather to make it work.” (Mark Funkhouser)

Making Government Work with Jobs-to-be-Done

The first question we ask is: who is the customer?

For government to work, we will have to understand what the needs of its constituents are. Unfortunately, a common language for communicating a need does not exist.

Consequently, while many government employees may have “customer” knowledge, agencies and departments rarely have a complete list of agreed upon constituent needs. Is there anyone in your agency that knows all the constituent’s needs? Is there agreement across the organization on what the constituent’s needs are? Is there agreement on which needs are unmet? If not, then how can there be agreement on what services to provide?

How do we begin to understand what is needed if we can’t agree on a shared purpose? The truth is government agencies routinely try to satisfy constituent needs without a clear definition of what a need even is. Before a government can succeed, leaders must agree on what a need is—and the types of needs that customers or constituents have.

The key to solving this mystery lies in Jobs-to-be-Done Theory.

Who is the Customer? Who is the Constituent?

Unlike business, the government does not get to select which customer segments to serve and which segments to ignore. Government must serve all its citizens and constituents. When it fails to do so, it becomes dysfunctional.

By definition, governance is a balancing act between the various requirements and needs of the different constituents. Our policy-making must be driven by this idea of balance if it is to create sustainable and long-term success.

Let’s ask again: who is the customer? Who are the constituent, the stakeholders that our government is accountable to?

Jobs-to-be-Done Theory provides a framework for (i) categorizing, defining, capturing, and organizing all your stakeholder needs, and (ii) tying stakeholder-defined performance metrics (in the form of desired outcome statements) to the Job-to-be-Done.

Once we understand what the needs are for each stakeholder, then the job of governing becomes a matter of prioritization.

With a complete set of constituent needs in hand, the agency or department is able to determine which needs are underserved and overserved, decide which strategies to pursue, simplify ideation, test concepts for their ability to get a job done in advance of their development, and align the actions of the agency to systematically create and deliver constituent value.

Different constituents will have different ideas on what they value.

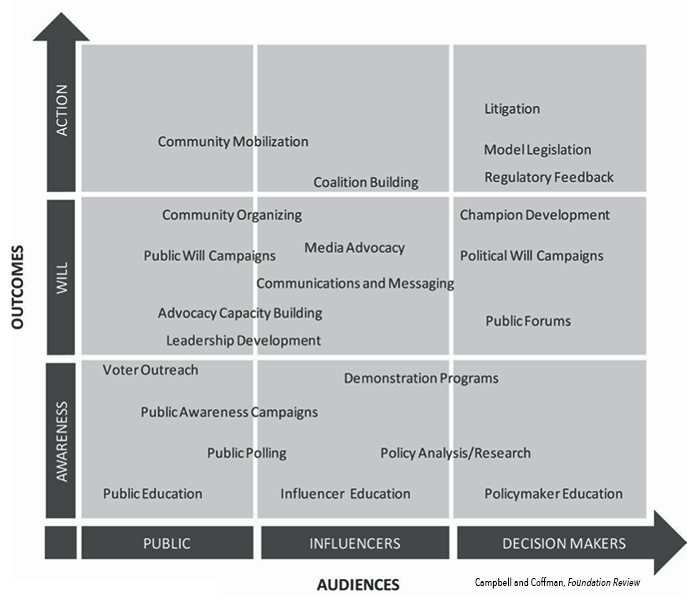

For simplicity, we’ll divide our stakeholders into three categories: the public, influencers, and decision-makers. Each of these will categories or segments are made up of a wide assortment of interests, with their own agendas and vote-banks.

What Outcomes Do We Want?

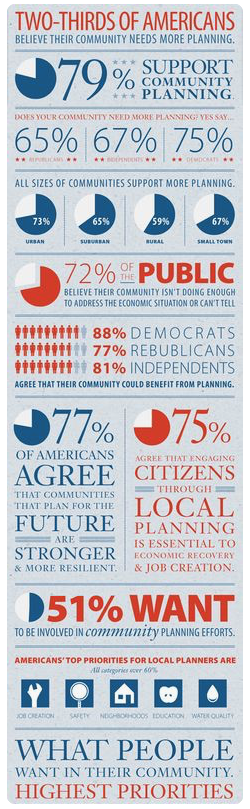

Applying Jobs Theory has the potential to remove or significantly diminish the partisanship we see across our communities today.

A poll conducted by the American Planning Association asked if a community plan – defined as a “process that seeks to engage all members of a community to create more prosperous, convenient, equitable, healthy and attractive places for present and future generations” – would benefit the community, 79 percent of respondents agreed. And that included a broad political spectrum with 88 percent of Democrats, 77 percent of Republicans, and 81 percent of independents in agreement.

A poll conducted by the American Planning Association asked if a community plan – defined as a “process that seeks to engage all members of a community to create more prosperous, convenient, equitable, healthy and attractive places for present and future generations” – would benefit the community, 79 percent of respondents agreed. And that included a broad political spectrum with 88 percent of Democrats, 77 percent of Republicans, and 81 percent of independents in agreement.

Respondents were asked to rank the top five factors that make up an “ideal community.” The results:

- Locally owned businesses nearby

- Being able to stay in the same neighborhood while aging

- Availability of sidewalks

- Energy-efficient homes

- Availability of transit

My point is this: when we focus on outcomes, we find that partisanship is not as pronounced.

Furthermore, when defined correctly, a functional Job-to-be-Done has three unique and extremely valuable characteristics:

First, a job is stable; it doesn’t change over time. It’s the delivery vehicle or the technology that changes. Through this decades-long evolution of drastically changing technology platforms, the Job-to-be-Done has remained the same. The job is a stable focal point around which to create constituent value.

Second, a job has no geographical boundaries. People who live in the USA, France, UK, Germany, South Korea, China, Russia, Brazil and Australia have many jobs in common that they are trying to get done. The solutions they use to get those jobs done may vary dramatically from geography to geography, but the jobs are the same. The degree to which the constituent’s desired outcomes are underserved may also vary by geography, depending on the solutions they use, but their collective set of desired outcomes are the same. Consequently, knowledge of the Job-to-be-Done in one geography can be leveraged globally. This has implications on serious implications for good governance practices and learning.

Third, a job is solution agnostic. The job has no solution boundaries. This means that a deep understanding of the job will inform the creation of a solution that combines all service components. It also informs a digitization strategy—ways to use technology to get a job done better.

Innovation in Government

An effective government innovation process must produce answers to the following questions:

- Who is the customer or constituent?

- What job is the constituent trying to get done?

- What are the constituent’s desired outcomes?

- Do segments of constituents exist that have different unmet outcomes?

- What unmet outcomes exist in each segment?

- How well do our services address the unmet outcomes?

- What segments and unmet outcomes should we target for improvement?

- How should we define our constituent value proposition?

- How should we position our existing and future services?

- What new services must we create?

- How do we measure success?

For a government agency or department to be successful at innovation, this means it must not only know all the needs of its various constituents, but it must be able to determine which needs are unmet. It must also be able to understand the segments with different unmet needs. These are the insights that enable the innovation process to become more predictable. Without these insights innovation remains a game of chance. Having them changes everything.

Outcome-Driven Policy

The problem with change in government is that we lack “constancy of purpose.” We rarely find support for long-term policy making for various reasons – ranging from ideology to budgetary constraints, to community outcry.

What is required is alignment, and the easiest way to establish long-term alignment is to focus on the outcomes we want and have agreement on.

Outcome-driven policy gets us aligned with the results we seek before we decide how to achieve these results.

This is where today’s process fails us. Once an agency knows all its constituents’ needs, which of those needs are underserved and overserved, and what unique under-and overserved segments of constituents exist, it must decide if and how it will serve each segment. For example, department leaders would want to determine if they should (i) add a new feature set to its existing offering, (ii) develop a new alternative offering, (iii) create a new platform-level solution that gets the job done significantly better, or do something else entirely.

Our work with government agencies shows us that disruptive innovation can provide tangible benefits, but only when aligned with a Jobs-to-be-Done framework. This is something we will explore in a separate post.